Role of Adenovirus in medicine: pathogens, predators

With advances in molecular biology informing recent developments in vaccinology, gene therapy, and other fields of medicine, human adenoviruses (HAdVs) have been of primary importance in medical research. A recent review in Trends in Molecular Medicine looks at the promises of HAdVs, their potential dangers, and future challenges.

The consequences of human adenovirus (HAdV) infections are

generally mild. However, despite the perception that HAdVs are harmless,

infections can cause severe disease in certain individuals, including newborns,

the immunocompromised, and those with pre-existing conditions, including

respiratory or cardiac disease. In addition, HAdV outbreaks remain relatively

common events and the recent emergence of more pathogenic genomic variants of

various genotypes has been well documented. Coupled with evidence of zoonotic

transmission, interspecies recombination, and the lack of approved AdV

antivirals or widely available vaccines, HAdVs remain a threat to public

health. At the same time, the detailed understanding of AdV biology garnered

over nearly 7 decades of study has made this group of viruses a molecular

workhorse for vaccine and gene therapy applications.

Introduction

HAdVs infect only humans, a pattern common to these highly

species-specific viruses. All vertebrates are susceptible to these

non-enveloped double-stranded DNA (dsDNA)-containing viruses.

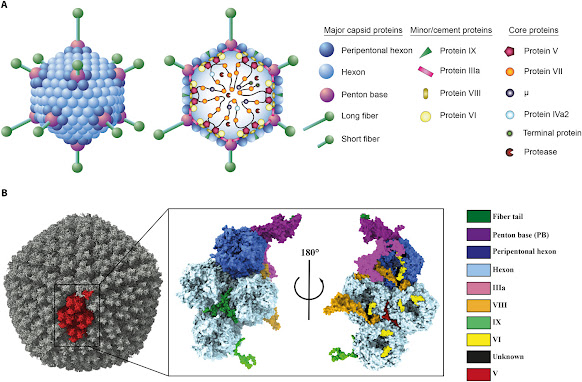

HAdVs have seven capsid proteins, three major and four

minor, and have been grouped into seven species, totaling 110. This

classification is both genotypic and phenotypic. Different HAdVs infect

different tissues, leading to variations in the clinical features of infection.

HAdVs have been used for medical research for approximately

70 years, with a wealth of data available on these tiny particles. This lends

confidence to scientists who use these viruses as vectors for various

applications, including vaccine delivery or gene therapy.

Timeline of HAdV-related knowledge

HAdVs were first isolated back in 1953 from healthy people's

tonsillar and adenoid tissue. The following year they were found in military

individuals suffering from acute respiratory disease, marking the first such

pathogen isolated since the 1930s, when the flu virus came to light.

It was then discovered to have oncogenic potential in some

species. It was used to create a new cell line for biomedical research but also

sparked a long immunization campaign for US military personnel. Meant to

control widely spreading respiratory illness, it succeeded remarkably well

until 1996-1999, when it was ceased for non-medical reasons. Repeated fresh

outbreaks led to the restarting of military vaccination in 2011.

In 1993 it came to be used for therapeutic CFTR gene delivery

in cystic fibrosis, the first effective human gene to be used in vivo for human

gene therapy. Its characterization also led to the important discovery of

messenger ribonucleic acid (mRNA) splicing, which won the 1993 Nobel Prize.

In 1999, a gene therapy trial-related death occurred,

putting the brakes on further research in this field. A C5 strain gave rise to

the first approved oncolytic virus in 2005. Almost 200 trials are ongoing of

adenovirus-based therapeutics and vaccines.

It was in 2020 that the first adenovirus vaccine gained

approval, against the Ebola virus, for use in exceptional circumstances.

Several more were developed the next year for use in the ongoing coronavirus

disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic.

Emerging variants

HAdV is non-seasonal and spreads rapidly within groups

within closed or separate facilities, including barracks, hospitals, or even

daycare centers. Most of these go unnoticed, but a few have gained attention

because of the severity of the disease and some deaths among immunocompromised

or frail individuals in the group. Some people without known disease and a

normal immune system have also died from these infections, albeit rarely.

This has led to identifying some recombinants and new

variants among HAdVs. This introduces genetic diversity, which could favor

transmission or virulence by introducing new functional traits.

Novel endemic variants began to be identified, including

HAdV-B14p1 in the early 2000s and B55 in 2006. The latter is a Trojan horse,

incorporating a B11-neutralizing epitope and a pathogenic B14 backbone. It

gained attention because of the unusually high frequency of pneumonia and acute

respiratory distress among people with apparently good health, with

higher-than-expected fatality rates as a result, compared to the parental B14

strain.

Similarly, the B55 variant arose from the recombination of

B11 and B14 strains and shows increased pathogenicity.

Soon after, in 2013, the E4 strain was recognized to be of

zoonotic interspecies origin. Recently, this strain was found to have acquired

gain-of-function mutations adding a key replication motif, nuclear factor 1

(NF-1), absent in the parental E4 strain but required for efficient replication

within human host cells.

This allows the new variant to replicate better and enhance

transmission, explaining the global spread of E4 in recent times. Again, the

E1B-19K gene deletion mutant could increase the inflammatory response to HAdV

infection.

Other zoonotic HAdVs are also being reported, and some researchers suggest repeated human-animal interspecies leaps occur with several recombinations.

Overall, a growing emphasis has been placed on exploring the potential of nonhuman AdVs to cross species barriers and understanding their interactions with the human immune system.”

Detection of HAdVs

The go-to technology for HAdV typing is the polymerase chain

reaction (PCR) nucleic acid amplification test (NAAT), which also helps to

monitor emerging variants. However, current methods have their limitations,

calling for next-generation sequencing and whole-genome sequencing (WGS),

coupled with phylogenetic analysis, for epidemiological insights into outbreaks

and infection control.

Meanwhile, some scientists have shown that the virus can

leave infected cells following replication both by lytic and non-lytic methods,

which could lead to quite different results clinically.

Clinical importance

HAdVs are largely considered harmless infectious agents but

can cause dangerous infections in those with immature or weakened immunity.

This could include neonates or very old people, those suffering from chronic

respiratory or cardiac illness, and those with weakened immunity due to various

disease conditions or taking immunosuppressive medications.

Conversely, with weakened immunity, the infection may become

serious, causing hepatitis or pneumonia, which may ultimately be fatal in a

small proportion of cases. HAdV can also cause epidemic keratoconjunctivitis

(EKC), most commonly due to the D8 variant. EKC is highly infectious and severe

and may take months or years to resolve completely. In some cases, vision may

be permanently impaired.

Eight of ten HAdV infections occur before the age of five

years. Acute respiratory infections requiring hospitalization are commonly due

to B3 and B7 strains, especially the latter, which replicate faster and cause a

greater release of inflammatory cytokines and airway inflammation.

New HAdV outbreaks have been traced to variants with greater

virulence, often arising from animal sources (zoonotic infections) or

recombination of human and animal adenoviruses. This could lead to more severe

diseases, for which the world is poorly equipped without antivirals or vaccines

approved for clinical use or that are widely available.

For instance, pediatric hepatitis is suspected to be due to

the coinfection of HAdV and adeno-associated virus (AAV), the latter being the

actual pathogenic agent in this case.

Almost all humans are infected at least once by the time

they complete their sixth year of life. These infections, especially with HAdV

A and D, are mild or asymptomatic. Such infections comprise a tenth of

childhood respiratory infections, mostly due to HAdV types 1-7.

The spread of the virus is respiratory, via droplets or

surface contamination, including directly to the eye to cause

keratoconjunctivitis; or by feco-oral transmission, including through food and

water. The time to clinical disease varies between two days to two weeks.

The immune response

A robust immune response typically leads to complete

resolution within a week or ten days. This involves innate humoral and cellular

immunity, as well as adaptive immunity. Innate immunity causes the release of

inflammatory cytokines, triggering antiviral responses in neighboring cells

while also hindering viral entry and enhancing the phagocytosis of viral

particles. Excessive inflammation may be linked to severe pneumonia following

HAdV infection.

The presence of cross-reactive T cells is important when

developing AdV vectors that will resist inactivation by host immune defenses.

Innate immunity memory, or trained immunity, mediated by broadly protective

memory macrophages, is being suspected to prevent HAdV reinfection.

Even after clinical recovery, the virus may be shed from the

gut and airways, for over 50 days, with immunocompromised people showing still

more prolonged shedding. Children with HAdV pneumonia shed HAdV-B7 and -B3 for

~100 and ~50 days, respectively.

This differentiates HAdV from other respiratory viruses in

children, such as the flu virus, which is shed for a mean of 18 days, and

respiratory syncytial virus at only four days. It also highlights the need for

more prolonged implementation of infection control measures in hospitals and

the community during such outbreaks.

Dormant or subclinical infection is also known, especially

in immunocompromised individuals, with disseminated viral disease in the

adenotonsillar tissues, the gut, and other tissues. This may affect clinical

outcomes such as chronic lung disease, heart disease, or even immunologic

reactions like graft-versus-host disease (GVHD).

Treatment

Despite their considerable toxicity, there are no specific

antivirals for HAdV infection, with broad-spectrum drugs being used for

whatever benefit they offer. For this reason, high-risk patients are routinely

monitored for HAdV infection following stem cell transplants.

New therapeutic approaches include drug repurposing, the

potential of T-cell therapy specific to this virus, and monoclonal antibodies.

Conclusion

As the scope and severity of HAdV disease become more

apparent, global collaborative surveillance is necessary to detect and control

outbreaks. The mechanism of disease and of transmission, the results in terms

of the host response, and new preventive and treatment strategies, are areas of

research that need to be addressed.

Journal reference:

MacNeil, K. M. et al. (2022). Adenoviruses in medicine:

innocuous pathogen, predator, or partner. Trends in Molecular Medicine. doi:

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molmed.2022.10.001

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1471491422002611

.jpg)

.jpg)

No comments