Insufficient deforestation to meet climate goals

Countries are failing to meet international targets to stop

global forest loss and degradation by 2030, according to a report. It is the

first to measure progress since world leaders set the targets last year at the

26th United Nations Climate Change Conference of the Parties (COP26) in

Glasgow, UK. Preserving forests, which can store carbon and, in some cases,

provide local cooling, is a crucial part of a larger strategy to curb global

warming.

The analysis, called the Forest Declaration Assessment,

shows that the rate of global deforestation slowed by 6.3% in 2021, compared

with the baseline average for 2018–20. But this “modest” progress falls short

of the annual 10% cut needed to end deforestation by 2030, says Erin Matson, a

consultant at Climate Focus, an advisory company headquartered in Amsterdam,

and author of the assessment, published on 24 October.

“It’s a good start, but we are not on track,” Matson said at

a press briefing, although she cautioned that the assessment looks at only one

year’s worth of data. A clearer picture of deforestation trends will emerge in

successive years, she added.

The assessment, which was carried out by a number of

civil-society and research groups, including the World Resources Institute, an

environmental think tank in Washington DC, comes as nations gear up for the

next big climate summit (COP27), to be held in November in Sharm El-Sheikh,

Egypt. Scientists agree that in order to limit global warming to 1.5–2 °C above

preindustrial levels — a threshold beyond which Earth’s climate will become

profoundly disrupted — deforestation must end.

Tropical forests are key

To track deforestation over the past year, the groups

analysed indicators such as changes in forest canopy, as measured by satellite

data, and the forest landscape integrity index, which is a measure of the

ecological health of forests. The slow progress they found is mainly

attributable to a few tropical countries where deforestation is highest (see

‘Progress report’). Among them is Brazil — the world’s largest contributor to

tree loss — which saw a 3% rise in the rate of deforestation in 2021, compared

with the baseline years. Rates also rose in heavy deforesters Bolivia and the

Democratic Republic of the Congo, by 6% and 3%, respectively, over the same

period.

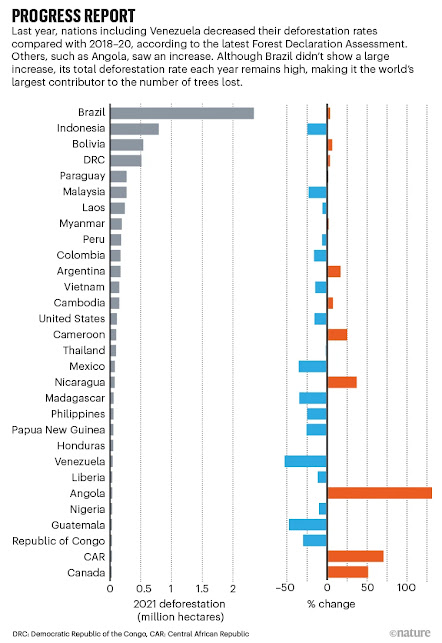

Progress report. Charts showing deforestation by country in

absolute terms, and as percentage change.

The loss of tropical forests, in particular, is worrisome

because a growing body of research shows that besides sequestering carbon,

these forests can physically cool nearby areas by creating clouds, humidifying

the air and releasing certain cooling molecules. Keeping tropical forests

standing provides a massive boost to global cooling that current policies

ignore, says a report, “Not Just Carbon”, released alongside the Forest

Declaration Assessment.

A region made up of tropical countries in Asia is the only

one on track to halt deforestation by 2030, according to the assessment (see

‘Movement towards goal’). The region cut the rate at which it lost humid,

old-growth forests last year by 20% from the 2018–20 baseline, mostly thanks to

large strides made by Indonesia — normally one of the world’s largest

contributors to deforestation — where the loss of old-growth forests fell by

25% in 2021 compared with the previous year.

Efforts by the government and corporations in Indonesia to

address the environmental harms of palm-oil production were key to progress,

the assessment says. For example, as of 2020, more than 80% of palm-oil

refiners had promised not to cut down or degrade any more forests. And in 2018,

the Indonesian government imposed a moratorium on new palm-oil plantations. But

the ban expired last year, raising concerns that progress might eventually be

reversed.

Finance lagging

Global demand for commodities such as beef, fossil fuels and

timber drive much of the forest loss that occurs today, as industry seeks to

clear trees for new pastures and resource extraction. Matson said that many

governments haven’t introduced reforms, such as protected-area regulations or

fiscal incentives to encourage the private sector to safeguard forests, and

that this is stalling progress.

In particular, nations are lagging behind in terms of fiscal

support for forest protection and restoration. On the basis of previous

assessments, the report estimates that forest conservation efforts require

somewhere between US$45 billion and $460 billion per year if nations are to

meet the 2030 goal. At present, commitments average less than 1% of what is

needed per year, it concludes.

Matson said that nations need to improve transparency on

financing by setting interim milestones and publicly reporting progress.

Michael Wolosin, a climate-solutions adviser at Conservation International, a

non-profit environmental organization headquartered in Arlington, Virginia,

would like to see donor countries recommit to their forest finance pledges at

COP27 this year.

However, Constance McDermott, an environmental-change

researcher at the University of Oxford, UK, cautions against focusing too much

on “estimates of forest cover change and dollars spent”. Social equity for

Indigenous people and those in local communities should be part of discussions

relating to deforestation, but is mostly missing, she says. These communities

are the best forest stewards, and more effort is needed to support them by

strengthening land rights and addressing land-use challenges that they

identify, she says.

Otherwise, McDermott warns that “global efforts to stop

deforestation are more than likely to reinforce global, national and local

inequalities”.

https://forestdeclaration.org/resources/forest-declaration-assessment-2022/

No comments